Looking backward to move forward

I thought I was bad at the law. Turns out I was just playing the wrong game.

Last year, I wrote an article about the personal factors behind my career pivot. There, I alluded to choosing work I enjoyed instead of purely for the exit options. Today, I’ll explain how I figured that out. In short, I had to look backward to all of my experiences to understand what I enjoyed and where my talents were.

There was a time in my mid to late twenties when I thought my biggest career wins—making law review, landing a job at Sullivan & Cromwell, securing a federal clerkship—were proof that hard work could overcome anything. I saw them as moments where I just happened to push harder than everyone else. And to be clear, luck and privilege played a role. I had access, timing, and support that many people don’t, and I don’t want to pretend otherwise.

But now that I’m in my early forties, looking back, I can clearly see that all those wins share the same origin story. They didn’t happen because I was the most gifted person in the room. They happened because of strengths I didn’t know how to articulate yet: The ability to connect with people, read & interpret unspoken dynamics, and nudge people toward decisions.

For years, I treated those strengths as irrelevant to my career. It wasn’t until much later that I realized they were the through-line of my entire career; and that every so-called “pivot,” including moving into sales, was really just a return to what I’d always been good at.

This article attempts to describe how I figured that out and why, if you’ve ever felt slightly out of place in your own career, hopefully you’ll end up seeing your path differently by the end.

The First Signs My Real Strength Was Something Else

It all started during my first year of law school. I met a classmate—let’s call him Jack—who was friendly & chill, and seemed like a good person to study with. I spent hours preparing for our first session together. I took meticulous notes during class, outlined everything we covered, used every supplement I could find, and put in hours of prep just for that meeting.

Jack showed up with nothing prepared. No notes, no outlines. He casually talked through every concept off the top of his head, with a level of clarity that made my preparation look pointless. When I asked how he remembered it all, he shrugged and said he just listened carefully in class. For me, it was a devastating revelation: The first person I happened to work with was operating at a level I couldn’t touch, even with massive effort.1

As the weeks went on, I realized my class was full of people like Jack. People who absorbed black letter law instantly and wrote thousands of words under time pressure effortlessly. I didn’t have that.So I defaulted to what I knew—sacrificing my social life and working really hard.

But while I was fixated on what I didn’t have, I completely missed the talents I did bring to the table. They didn’t show up on exams, but they were very real. I could gain people’s trust quickly, and make friends from different groups easily. I naturally made people feel comfortable in an environment that was anything but. I could rally people to go out for drinks (or stay in to watch NBA games) without significant effort.2

In hindsight, those were signs of unique interpersonal skills; just a completely different kind of talent than what law school rewarded. And while it didn’t help me much during the hyper-competitive 1L year, it became invaluable later in my career.

Those early moments planted a seed, even if I didn’t see it at the time: my strengths weren’t in mastering the law. They were instead persuasion in the broadest sense—connecting with people, earning trust, and moving individuals & groups toward action. It would take me years to understand how important that distinction actually was.

Hustle Was a Signal, Not Just a Survival Tactic

Coming out of my first year, I carried a simple & neat story about myself: I wasn’t naturally talented, so I had to rely on effort. Anytime I broke through, I credited it to working harder. Looking back, I now recognize that wasn’t the full picture. The moments where I advanced weren’t just about grinding out academic results—they were moments where I leaned into strengths I didn’t realize I had.

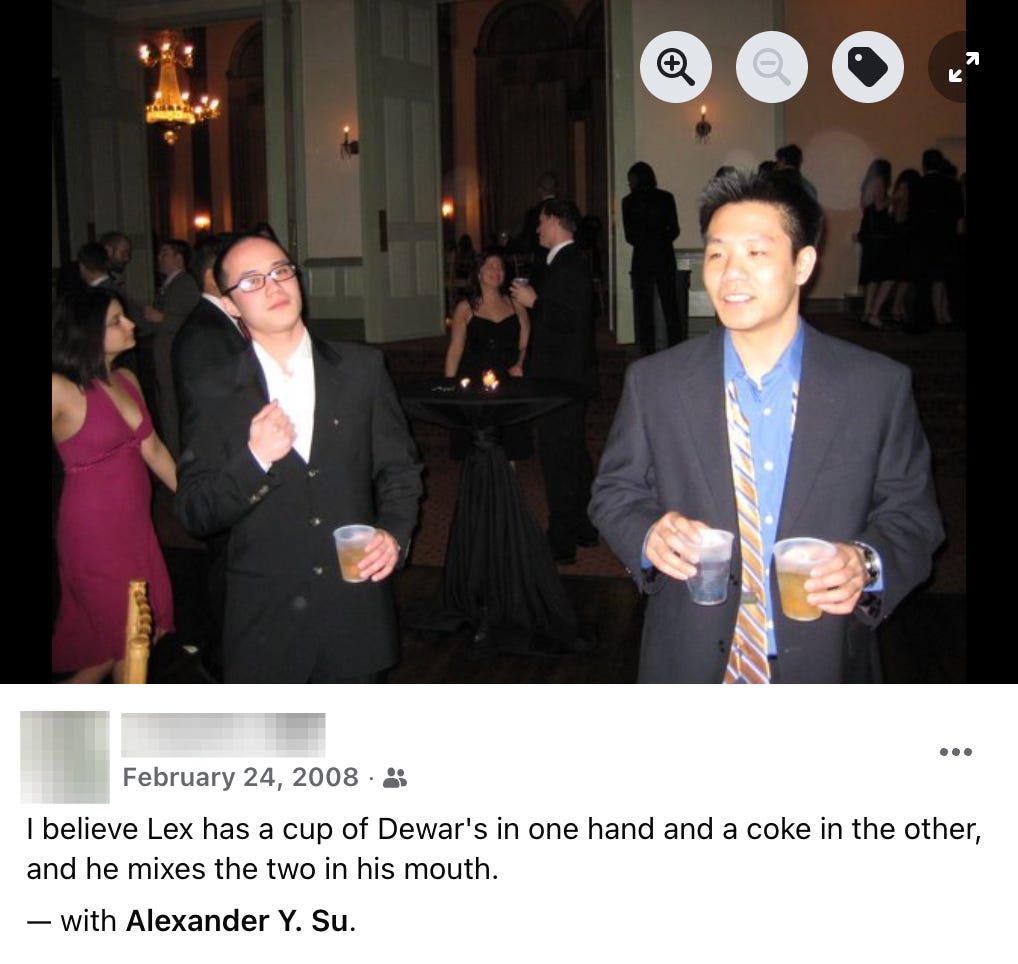

An instructive example was during on campus interviews (OCI). My GPA was below the cutoff for Sullivan & Cromwell, so on paper I shouldn’t have had a shot.3 By that point, I had just written onto law review rather than qualifying by my grades. Law review was an important credential that helped me get in the door, but it also fed a quiet insecurity. Internally I felt like an imposter who had somehow acquired credentials I didn’t deserve. I distinctly remember walking into OCI interviews convinced the firms would eventually see right through me.

I knew I had to do something different. Showing up and just talking about myself—the advice I’d received from 3Ls and other well-meaning people—didn’t feel sufficient. So for S&C, I decided to arrive at the “hospitality suite” where interviews took place, and talked to anyone I could. I ended up chatting with a junior associate who was tasked with greeting people. Most candidates ignored her because she wasn’t a decision-maker, but I thought her story was interesting. So we talked like normal people, without all the forced formality of an interview.

When I then interviewed with the partner, the conversation felt unremarkable. We had little in common, and I walked out assuming it was over. But later that evening I learned I’d been selected to advance to the “callback” stage, where they’d invite me to meet with more lawyers at their NYC office. At S&C, a “callback” meant that the offer was yours to lose.4

As it turned out, the reason wasn’t my grades or some brilliant interview moment—it was that the associate had championed me. She told the hiring partner that my personality came through in a way that mattered, and it outweighed the credential gap.5

At the time, I thought I’d gotten lucky. But looking back, it wasn’t luck alone. It was the ability to connect with someone and make them feel at ease—even while I was quietly terrified of being exposed. What I had always labeled “hustle” was really something else: understanding people, spotting unexpected opportunities, and creating momentum from zero.

Law school didn’t reward those skills directly, but every time the stakes were high, they showed up. And over time, those moments formed a pattern—one that hinted my strengths were never about legal acumen. They were about connection and persuasion long before I ever considered a career in sales.

Where I Misread My Own Strength

Even as these patterns started to appear, I didn’t know how to interpret them. I kept assuming my advantages were temporary or accidental. And because I didn’t understand what my real strengths were, I kept putting myself into situations where those strengths didn’t actually matter.

A perfect example was when I ran for Editor-in-Chief of the law review. I treated the whole thing like a persuasion exercise—building support, talking to the 3Ls on the editorial board, thinking it was a popularity contest I could “win.” What I completely misread was the structure of the game. It wasn’t a broad election at all. The outgoing EIC was the real decision-maker; everything else was theater.6

On top of that, there was some self-delusion mixed in. The application process required us to rank our interest in various editorial board roles. I convinced myself that saying that I’d take any job they offered would somehow increase my chances of getting the top one. I even convinced myself I would genuinely be happy with anything. When I lost, the result made the reality clear: they didn’t give me my second choice, or third, or even fourth—they gave me the role I had ranked dead last. Which I immediately realized I didn’t want.

My summer associate experience had a similar dynamic. Instead of leaning into the strengths that had helped me up to that point—curiosity, connection, showing personality—I tried to blend in. Some of it was the culture shock of being at S&C. I was surrounded by people from extremely privileged backgrounds, and even though there were plenty of Asian associates, I still felt a cultural distance from everyone that I couldn’t quite define.7 My instinct was to avoid rocking the boat. The result was predictable: I didn’t stand out. I worked hard, fit in fine, but that was it.

Both situations had the same root problem. I was applying my strengths in the wrong arena, and sometimes in the wrong way. I kept trying to play games I shouldn’t have been playing—games optimized for credentials and prestige—when my edge lived somewhere else entirely.

The Moment I Could Finally Name It

For most of my early career, I kept trying to succeed on terms that weren’t mine. I chased the roles, credentials, and validation that the legal world told me mattered, and every time something didn’t click, I assumed it was because I needed to work harder or make bigger sacrifices.

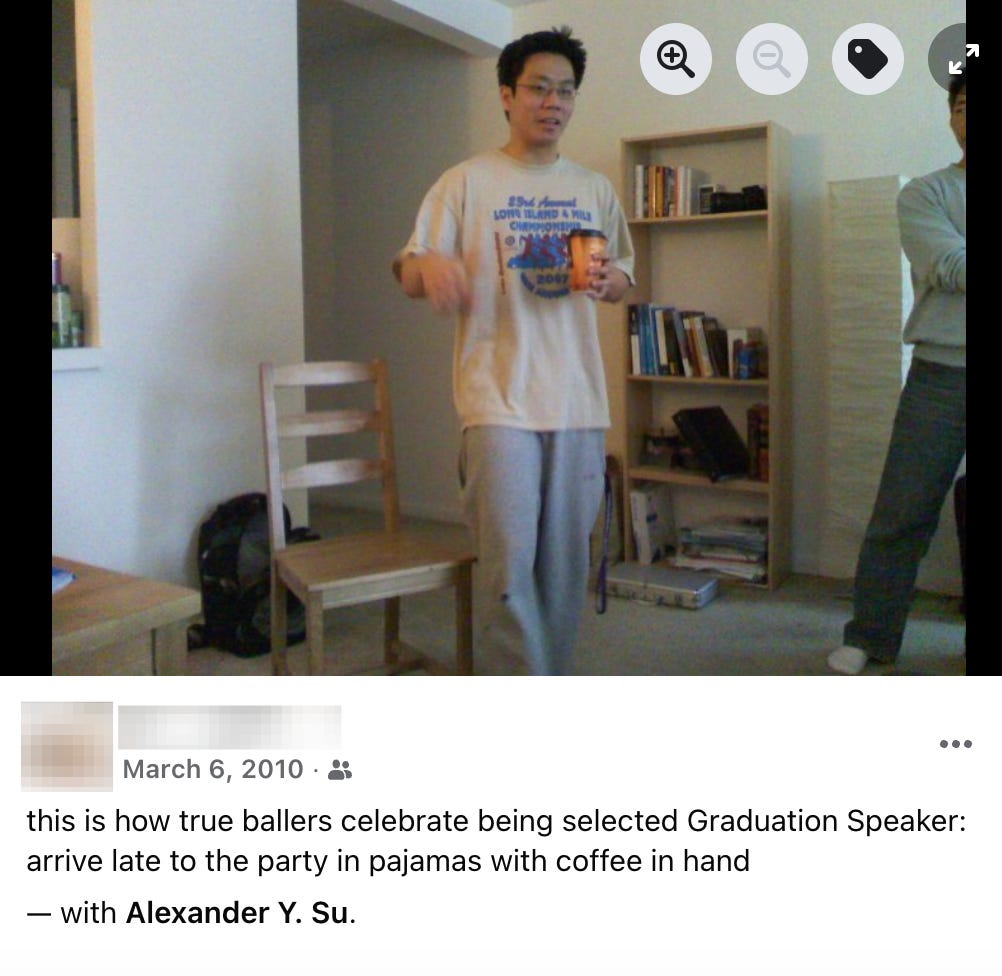

The first real clue came from something I initially treated as insignificant: becoming my class’ graduation speaker. It wasn’t based on grades or by appointment; it was based on an election. On a whim I decided to run. It wasn’t a coveted role like law review leadership, and I certainly didn’t see it as career-defining. I just thought it might be something cool and fun to do.

There were two stages to that experience.

The first was campaigning for the position itself. Unlike the law review process, which had a single decision-maker, the graduation speaker appointment depended on a broad base of support. It was an election. Nearly twenty classmates ran, and I immediately grasped the implications. If I could mobilize my friends from all the different groups quickly, I could immediately secure a plurality of support.8 What started casually became something I pursued with real focus and intensity, even if I didn’t yet understand why.

The second stage was preparing the speech. This part scared me far more than running in the election. Standing in front of a thousand people made me acutely aware of the responsibility that came with the platform. I felt a deep fear of wasting everyone’s time. Anyone who’s gone to a couple of graduations knows that student speeches can be painful. I vowed to deliver a speech that was both entertaining and memorable.

So I took the speechwriting process seriously. I kept the message simple and personal—how I ended up at Northwestern Law and how hard it had been to get there. I studied what worked, watched other graduation speeches on Youtube, borrowed structures, tested jokes, and practiced it in front of focus groups of friends from different circles. The goal wasn’t to impress. It was to respect the audience.

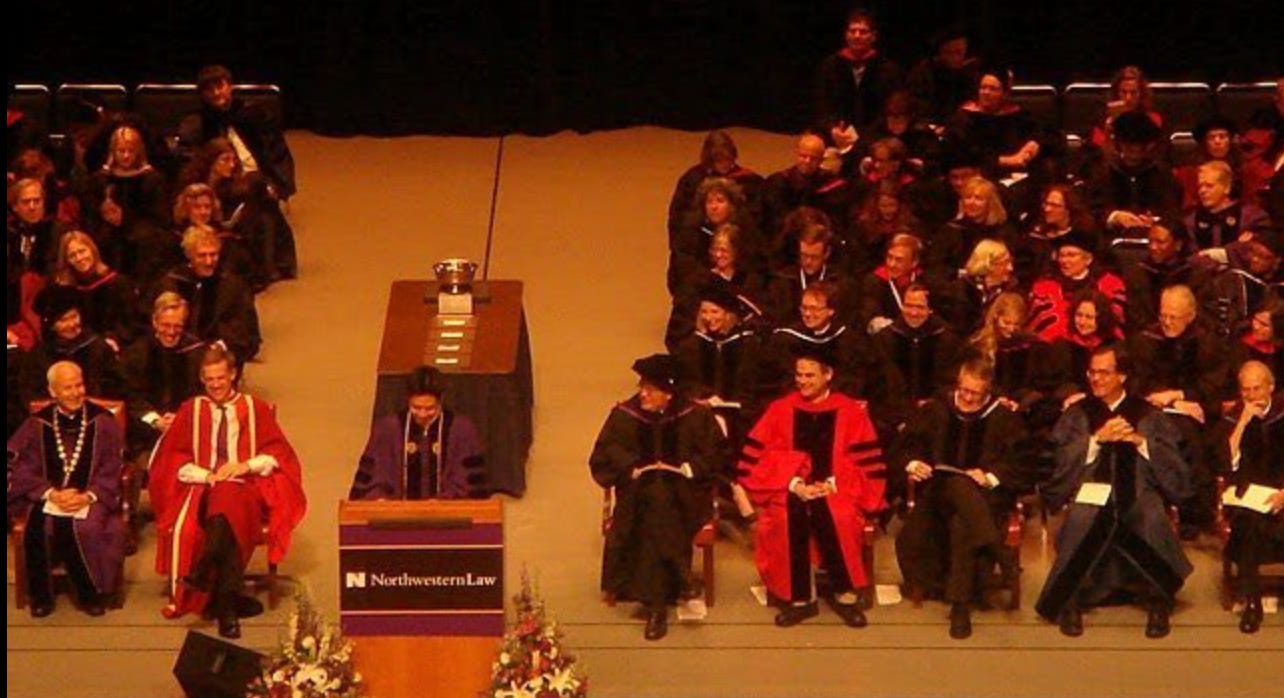

You can find the speech here, on Youtube. My delivery was imperfect and I was incredibly nervous throughout. Once I was done, I immediately walked off the stage because I wasn’t sure if people would clap very much—and I wanted to get back to my seat quickly before it died down. But when I got off the stage and looked up, I saw that every single one of my classmates were applauding.

And not just that—they were all standing.

The standing ovation wasn’t just gratifying. It unlocked unexpected upside. One of my professors, who had taught at the school for decades, remarked to me afterwards: “I have never seen a student speaker receive a standing ovation.” The professor then told me that he planned to call up his former student—whose nomination to the federal bench was pending—to recommend me as his first law clerk.

That was the moment the pattern became impossible to ignore. When the work revolved around persuasion in its broadest sense—people, trust, clarity, and decision-making—everything felt easier and my performance was superlative. Over time, it became clear that the same instincts that helped with my graduation speaker experience showed up elsewhere in my career in domains ranging from sales, to social media, to leadership/management.

Alignment, Not Reinvention

Once I saw that pattern clearly, it reshaped how I understood my career—and how I made decisions going forward. Law review opened short-term doors. S&C shaped my work habits and standards. The clerkship gave me a mentor and showed me how to combine high performance with kindness. Not a single one of those experiences were wasted.

But the realization underneath all of them also clarified something else. I didn’t need to keep playing the same games other people were playing just because they came with gold stars or impressed strangers. That insight directly informed my decision to eventually pivot into startup sales in 2016—and to remain in the legal ecosystem rather than abandon it entirely.

At times, it’s still hard to explain to people what exactly it is that I do. Most lawyers understand, but a lot of people (especially outside of the legal industry) don’t quite know how to put me in a box. “You’re a lawyer—but you decided to work in … legal staffing?” But over time I’ve come to believe there’s more real satisfaction—and more real glory—in doing excellent work in your chosen domain (no matter what it is) than trying to gain prestige for its own sake.

Pivoting out of law didn’t feel like a leap. It felt like alignment. Once I realized that, everything that came afterward was easier to understand.

Conclusion

Luck and privilege matter. Timing matters. I benefited from all three. But so does paying attention to patterns.

In my case, the achievements I was proud of early in my career—law review, S&C, the clerkship—didn’t happen because I mastered substantive law faster than everyone else. They happened because of strengths I had been using my whole life: persuasion, connection, trust, and an instinct for how decisions actually get made.

The moment I started focusing on those strengths, my career stopped feeling like a tug-of-war and started feeling like alignment. I didn’t reinvent myself. I recognized what had been true all along.

Here’s the takeaway from my long and meandering story: If you feel stuck or out of place, I highly recommend that you to look backward before you look forward. Look at where things felt easy. Where opportunities appeared that couldn’t be explained by credentials or randomness. You might find that the path you’re meant to take isn’t a sharp turn at all. but the one you’ve been walking toward for years, waiting for you to finally name it.

Good luck my friends.

Jack went on to graduate from the top of our class, won moot court, clerked for a federal judge, and landed a job at a top firm. He made partner at his firm years ago. As it turns out, he was one of the biggest stars of our law school class (and an incredibly kind person). What I’m trying to say is that I had just really bad luck pairing up with my first study partner.

To this day I don’t think I am particularly talented at mobilizing social groups. But I have had enough people close to me struggle with it to recognize that it may be a talent of mine. One of my brilliant classmates (who is now a partner at a major firm) once confided in me that he could not understand why no one would join him whenever he came up with a plan for our group. I wanted to point out the 4-5 different things that he was doing wrong, but then thought better of it—after all he didn’t seem to be looking for a solution, he just wanted my empathy. But that conversation made me realize that some things come to me intuitively. And may explain why I have always gravitated to community-building work (hosting Zooms during the pandemic, being the head of community development at Ironclad).

I did not realize S&C had a cutoff for Northwestern students until many years later when I served on the interview committee. But I could tell from the historical GPA-callback data provided by our career center, that it was highly unlikely for me to get a callback there.

I cannot overstate the importance of landing that initial callback. Nearly all law students who get callbacks get an offer for a summer associate position, and nearly every summer associate gets a full-time offer. Landing the plane on the callback meant I could potentially be set for the next 5-10 years, and potentially longer.

Some people who hear this story say “well of course they hired you, you were a law review editor at a top school!” However, I had unusually low grades for law review editor. OCI results were heavily based on GPA. Plus, S&C had a reputation for hiring purely on grades and less so on soft factors. Still does, I think. My odds of landing a callback there were very low according to historical data.

The position I ultimately took on was “special projects editor.” Which was a super vague role. Essentially, the former EIC wanted me to represent Northwestern in a multi-school academic initiative called “The Legal Workshop.” It was a lot of work for a goal I didn’t view as important. I am embarrassed to say that I intentionally did very little work on that initiative, in part because I was so upset/angry about the way I was treated during the ed board selection process. In retrospect that was the wrong way to approach things—I should’ve instead openly explained how upset I was and then declined the special projects editor position. Instead of what I ended up doing—which was accepting the position & shirking my responsibilities. It was a chapter of my law school experience that I’m not proud of.

It took me many years but I later realized that my experience was not unique. Lots of people felt like a fish out of water at S&C. Which is why I have tried to care less about “fitting in” as I’ve gotten older—better to be authentic to yourself because who knows? Maybe everyone else feels the same way.

This was a lesson I learned working on political campaigns. To win, you often need far fewer votes than you think. The more candidates there are, the more likely it is that you can win the entire election with just a small percentage of voters. So locking them in right away was key to victory—and speed mattered more than anything else. Once the graduation speaker ballot was out, I acted instantly to secure votes from my closest friends, which I believe ended up making all the difference.

There is so much that resonates here—thank you for sharing, Alex. I have had similar moments, which I would describe as “realizing what you thought was a weakness is actually a strength.”

Did you deliberately sit down one day to assess these patterns (e.g., in a “design your life” or similar exercise)? Or did the realization of your strengths just slowly come to an aha moment one day?

One of your best!

I really like how you were able to look back and find the ways you succeeded due to the skills you didn’t recognize at the time. The OCI example really hits that point home.