The line on the resume

And why the excessive focus on credentials extends beyond looking at where someone went to school

This is a free weekly email for Off The Record subscribers. If you’re interested in learning more about business development, consider upgrading to a paid subscription, which gives you full access to premium sales content.

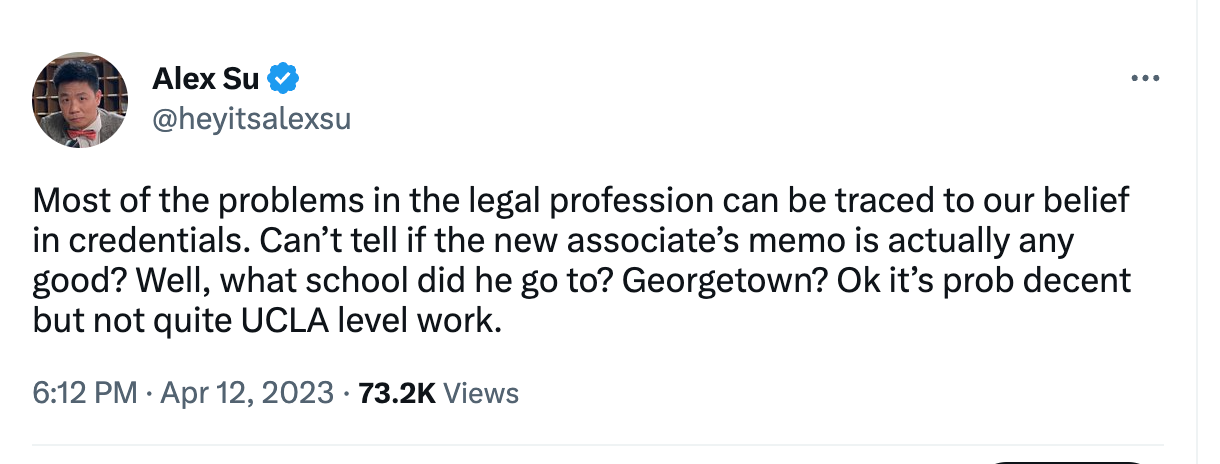

Earlier this week I posted a dumb tweet that got a bunch of views unexpectedly on Twitter:

It was dumb because while the first sentence was serious, the rest of it was a silly reference to the newly released U.S. News law school rankings, where UCLA moved up to #14 to oust Georgetown from the notorious “top 14” set of law schools.1

Lots of people rushed in to challenge what I said. Some pointed out that this is only an issue among the “top 1%” of the profession. Others said it’s only a phenomenon among “big city” practices, and doesn’t happen in smaller cities. Interestingly, sources ranging from Biglaw partners to law students took issue with the tweet.